In his new book, “Grace Can Lead Us Home,” my friend Kevin Nye discusses how Christians can better approach the issue of homelessness through a lens of grace. Pulling from his experience serving unhoused people in Los Angeles over the past 6 years, Nye re-centers the humanity of people experiencing homelessness. Over the course of the book, Nye explores many different avenues that might lead someone to become unhoused. It was simultaneously heart wrenching to read the stories of people he’s helped, while incredibly thought provoking when it comes to how we can do more, in terms of both caring for the unhoused, and preventing them from getting there in the first place. Nye’s approach is equal parts pragmatic and poignant, explaining the systemic causes, while also keeping in mind that the people experiencing homelessness are, in fact, still people, worthy of care, compassion, and support.

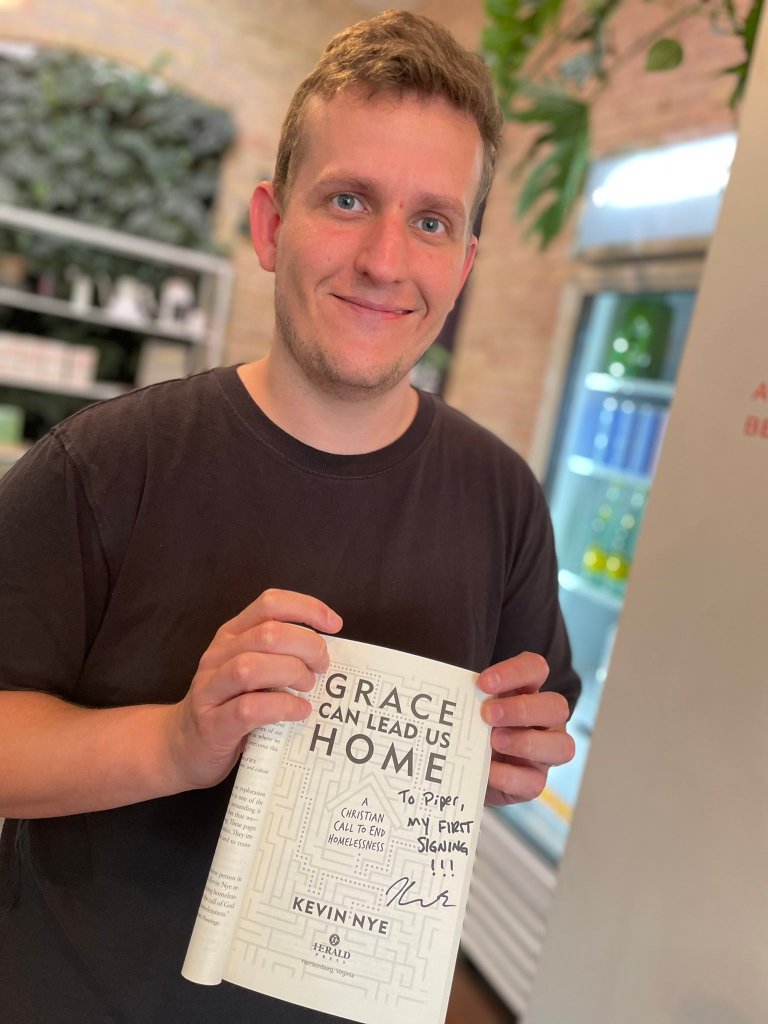

“Grace Can Lead Us Home” released August 9th, 2022, though I was lucky enough to get an advance copy for the sake of writing this review. Having cool friends doing cool things makes me feel extra super cool, so when I got coffee with Kevin the other day, I had him sign my copy. ✌️

Thus ends the cliff’s notes section of my review. If you’ve read one of my previous posts under The Reading Lamp, you know that these tend to be less “critical review,” and more “Pip reflects on all the things this book made them feel.” With that said, spoilers ahoy, so if you’d prefer to read it for yourself without my commentary…

Before we dig in, I want to give y’all a heads up. This book is classed a “Christian Living” book, so if Christian theology is something you don’t jive with, it may not be your speed. In painting a comprehensive image of the issue of homelessness, the book discusses topics that some may find triggering, including discrimination, mental illness, substance use and addiction, and death. Just wanted to make sure you were aware, in case you find these concepts to be challenging.

Kevin kicks off the book with a brief note on the language he uses when discussing the issue of homelessness. Rather than using the word “homeless” on its own, Nye opts to use person-first language, which emphasizes humanity and personhood first. By saying “person experiencing homelessness,” instead of “homeless person,” we also mark homelessness as a temporary experience.

Similarly, using “unhoused person” instead also helps shift focus to housing, which is a more tangible, political reality. To use the verb “housed” recognizes the responsibility a community has in ensuring that people have access to housing. Community and responsibility are some of the major themes throughout this book. Though it’s so easy to get caught up in our own lives and brush off the issue of homelessness as “not my circus, not my monkeys,” we have a responsibility to help those in our communities that may be experiencing homelessness.

One person Kevin asked about preferred language around homelessness bluntly responded, “I don’t care what you call us. What are you doing to help us?” In serving and advocating for those experiencing homelessness, our language matters far less than our action. What can we do actually do to help these people out of the challenging circumstances they find themselves in?

Aside from the titular concept of grace, a strong point that Nye emphasizes throughout the book is the importance of community and connection. From the get-go, Kevin anchors his approach not only in his experience working alongside the unhoused, but in Scripture. If you’ve spent any time in Evangelical spaces, you may be familiar with this verse:

“For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope.”

Jeremiah 29:11 ESV

I’ve always heard this verse used in conjunction with the prosperity gospel. God wants to have me specifically prosper. Kevin helps put this verse back into context, running back a whopping four verses.

“But seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.”

Jeremiah 29:7 ESV

Nye points out that welfare in both cases comes from the Hebrew “shalom,” a sense of holistic peace and completeness. As Kevin puts it, “The welfare God has for us is not merely a general promise of happiness and fortune, but is instead directly tied to the welfare of everyone around us.” Despite the individualistic mindset that a capitalist society has sown into us, prosperity isn’t simply for “me,” but something that hinges on our community at large. We cannot experience the fullness of our own welfare while those around us are struggling.

A loving, supportive community can do so much in the lives of those experiencing homelessness. There was a brief time, a whole week of my senior year of high school, where I did not feel safe living at home. Had it not been for the deep care my friends had for me, I wouldn’t have had a safe place to sleep. I wouldn’t have known if I would eat an actual meal outside of school. Because I had a community of people who didn’t want to see me struggle, I was able to weather that time of pain and uncertainty. Simply because I had people who cared about me as a person.

Many have been in more dire straits than I was at seventeen, finding themselves with nowhere to land, not just in terms of housing, but everything that comes with the idea of “home.”

While literal housing and tangible resources are essential, we would do well to recognize that the experience of homelessness entails a disconnection from more than just physical resources; it is isolating, dehumanizing, and traumatizing. However crucial the role of housing in ending homelessness, we cannot forget that the experience of being homeless also means a loss of the anything’s we associate with “home,” things as indispensable as safety, belonging, dignity, and hope.

“Introduction,” page 23.

I firmly believe that all people, regardless of who they are or what they may have done, are deserving of these basic things: peace, safety, happiness, kindness, love and respect. No one should have to struggle to earn these things, and yet, in our highly individualistic society, it seems we are always in competition to achieve this baseline. Some hold these things as a badge of honor. “I worked my ass off to get where I am, you should just buck up and do the same,” as if the have-nots are somehow morally inferior for landing where they are. I will never understand this mindset. Who are we to decide whether someone is deserving of their circumstances?

God has declared that we are worthy. Not on our terms, but on God’s.

If our welfare hinges on the welfare of our community at large, if our holistic, “shalom” welfare is tied to that of those around us, it springs a whole well of questions in my heart: Why aren’t we pushing harder against income inequality? Why do we allow so many to live in poverty? When will we redistribute wealth so that none have need, as shown in the church of Acts? When will we stop leaning into the lies of prosperity gospel greed? God doesn’t only want ME to prosper, but each and every one of us.

To Jesus, a person’s future is not dictated by what they have and have not done in their past. Jesus practices grace, interrupting and disregarding all our petty logic of who deserves what.

“Seeing and Being Seen,” page 44.

We are all human. We have all dropped the ball in one way or another, but that doesn’t make us any less deserving of a shalom kind of existence. However, this approach is counter-intuitive to the bent of justice and judgement that we’ve been accustomed to. “You do good, you deserve good. You do bad, you deserve bad. You cause hurt, you deserve hurt.” Shifting our mindset to be led by grace is so important, not just when it comes to people experiencing homelessness, but in interacting with people overall.

It is crucial that we recognize the role that grace plays in undermining our calculations about what people deserve.

Admittedly, my hands-on experience with the unhoused is incredibly limited. Mostly cash given at a stoplight before the traffic signal changes, nothing I would consider to be very impactful. During my time interning for a local mega-church, we went on a “mission trip” out to Sioux Falls, South Dakota. One of the outreach things we were meant to do was hand out sack lunches to unhoused people encamped at one of the city’s parks. To me, it felt very icky. Sure, a free-lunch is a free lunch, but when it comes with the strings attached of “let this 20-something talk your ear off about Jesus,” it felt incredibly intrusive to do.

Above all else, homelessness dehumanizes. It isolates, it discards, and it amplifies fear and anxiety. In your daily interactions with people experiencing homelessness, their homelessness is not truly at stake. Their humanity, though, is.

“Isolation and Connection,” page 77.

The kind of “world-changer” mindset that a lot of the interns carried into this outing was some flavor of saviorism, a hero complex that Nye points out to be inherently othering and hierarchal. Leading an interaction with “Let me, A Good Christiantm, tell you how Jesus can change your life, cuz obviously whatever you’re doing isn’t working for you,” is so incredibly disrespectful. With no context for what this person has been through, how can we expect to have any meaningful impact?

The most fulfilling moments of my work happen when the power dynamics of worker and client, or of privileged and needy, melt and give way to true human connection; when, with coffee mugs in hand, we bond over a favorite song, laugh together at a bad joke, or geek out over superhero movies. In these moments we see and are seen by one another, connected through the small but indispensable pieces that make up our whole selves. These connections have transformed how I see homelessness and those experiencing it, rinsing from my eyes the false belief that unhoused people deserve their circumstances, or that the are helpless without me.

“Seeing and Being Seen,” page 47.

Until we have a genuine connection with someone, we have no business giving our unsolicited opinions on how they can improve their life. We must see them as a person to be loved, not a problem to be solved. We cannot expect to make change without first having connection.

In his chapter on “Community and Solidarity,” Nye explores “one of the biblical passages most often deployed against the work of alleviating poverty.” (As a concept, it is absolutely wild to me to use the Bible to justify why other people deserve to suffer, but that’s an entirely different can of worms.) Jesus makes a comment which, in the NIV, is commonly rendered as “The poor you will always have with you.” This is often taken to mean “there’s always gonna be poor people, nothing to be done about it.” Nye argues that this cannot be a legitimate reading of the text, as it doesn’t translate this way in KJV, NASB, NRSV. Rather, these translations read “The poor you always have with you.” This tiny little change in verb tense from “will have” to “have” is important. It’s not that Jesus is diminishing people living in poverty to be an inevitability. He’s not attempting to gloss over them, or attempt to pull our attention from them. Instead, they are his primary audience, the very people He came to show us how to care for, and is reminding his disciples that the poor should always be with them, carried alongside them, moving through life together.

…pointing back to Deuteronomy 15:11, which reads, “Since there will never cease to be need on the earth, I therefore command you, ‘open your hand to the poor and needy neighbor in your land.’” The larger context of Deuteronomy 15 describes God’s vision for jubilee, a recurring redistribution of wealth and resources to even the playing field for those who have fallen into poverty.

“Community and Solidarity,” page 102.

While you may have never experienced homelessness, perhaps you know what it’s like to struggle financially, to live paycheck to paycheck, to question where your next meal may be coming from. For me, having been in such challenging places has made me more apt to open my hand to the needy, and give when I have the capacity. The way our world operates, there will always be a need to be filled, but if there’s anything I can do to help keep others from experiencing those same struggles I’ve been through, you can bet I will jump at the opportunity. To quote a hot take from my friend James, “we live in a world of have and have-nots, and if you are part of the collective ‘have,’ you cannot empathize with the ‘have-nots.’ One of the key parts of being spiritual is having empathy for others.” We best empathize with those with whom we share life experiences.

Jesus is inviting [his disciples] out of a mode of transactional giving and into communal solidarity. If disciples of Jesus are always among the poor, in community and communion, the needs of the poor will be recognized and met through mutual aid, rather than through the giving of money at a distance.

“Community and Solidarity,” page 102.

When we can connect with one another through the challenges life has thrown our way, it strengthens the bond of our communities. It strips the away the nature of “I’m giving to get something out of it,” whether that’s social leverage or simply a warm fuzzy “I did good today” feeling, and exchanges it for a motive of “I’m giving because I care about you as a person, and don’t want to see you struggle.”

We are created for relationships and communities; without these, we are incomplete. This commuion resists social norms, and upends economic division, enacting jubilee not as charity but as solidarity.

“Community and Solidarity,” page 103.

What does solidarity look like in action? It’s an awareness of the challenges those around you may be facing, and working to help them overcome them. I’ve been very general with using the word “struggle,” but let’s get into some specifics, which Nye dedicates entire chapters to, far more articulately than I ever could.

One of the biggest challenges that can land people in situations of homelessness is a lack of overall care for mental health. Especially in recent years, it’s become glaringly obvious that we are not equipped to adequately address mental health, whether that’s common conditions like ADHD, depression, and anxiety, or more complicated illnesses like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The system is rigged to favor neurotypical patterns of behavior, with little room for accommodation for those who fall outside the norm.

In many churches, mental illness is treated as a moral failing. I’ve even heard preached from the pulpit that people like me, who deal with ADHD, should just “confess that they have the mind of Christ, shut up, sit still, and pay attention.” Dismissing anxiety and depression with scripture was all too common. After all, how can you, a Christian, be depressed, when “the joy of the Lord is your strength,” right? Often, if someone struggles with mental health, it’s treated as them not “believing for their healing,” which is frankly ableist.

We need to become comfortable with the idea that there is no correlation between the amount of faith someone has and their mental health. However, there is a direct correlation between mental health and the amount of a community support a person has.

“Mental Health,” page 121.

With lack of access to affordable care, whether in terms of therapy or medication, many people have to navigate their mental health without any support. I know from experience just how isolating this can be. Something as simple as having someone who is open to listen to what you’re dealing with can do so much to make someone feel supported.

However, many who struggle with mental illness don’t have a support network. In trying to manage on their own, many turn to substance use to help ease their pain. As Nye says, “We must understand that people use drugs not because they are selfish and want to feel good, but because they are hurting and want to stop feeling bad.”

Substance use, even in regard to tobacco and alcohol, has largely been vilified by the Church. Addiction especially is treated as a moral failing, and not as the health issue it truly is. Really, people turn to substance use or fall into addiction in trying to achieve that baseline of feeling peace, feeling safe, feeling happy, feeling loved.

These basic human, spiritual needs often go unmet among people experiencing homelessness, especially those who are addicted. The crisis of overdose deaths prompts us not only to save as many lives as possible, but also to investigate how addiction manifests in the first place. In so doing, our imaginations are reshaped from resentment and judgement to grace, and this orients us rightly to being exploring how to help people recover.

“Addiction and Recovery,” page 150.

Rather than looking at those struggling and asking how they got themselves in the mess they’re in, grace calls us to do what we can to help lift them out of the circumstances. We exercise compassion when we act to keep others from enduring harm.

Nye explores how Jesus practices a form of harm reduction in John 8, in the story of the woman “caught in adultery.”

Jesus simply told the woman, “Go your way, and from now on do not sin again,” a nod to the hope that she would not find herself in the same precarious situation, yet he offered no condemnation, no prerequisite for a change in her behavior.

“Substance Use and Recovery,” page 136

Nye goes on to point out that, in line with Romans 5:8, “God demonstrates His own love for us in this: while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” At no point does the question of whether a person “deserves it” enter the equation. As long as we’re getting biblical, I was reminded of John 3:17, “For God did not send His Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world through Him might be saved.” If the Almighty Himself doesn’t judge us based on our actions, but still calls us worthy of love as we are, who are we to judge our neighbors before offering care?

“We must learn to regard people less in light of what they do or do not do, and more in light of what they suffer.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “Letters and Papers from Prison.”

Overall, Nye illustrates how living in communion and solidarity with our unhoused neighbors is simply an exercise in loving people well.

If “whatever you do for the least of these, you have done for me,” then spending time with the unhoused and the poor is spending time with Jesus. When this is done without worry and without a need to fix or achieve anything, God is near and hope is renewed.

“Abundance, Beauty, and Celebration,” page 160.

This book was a needed reminder of the humanity of those experiencing homelessness, and was incredibly informative of what we can do better to shift our mindset when it comes to advocating for them.

We must push for solutions that actually end homelessness, rather than simply push it out of sight and mind. Each chapter of this book has held these in tension: the large mountain moving work of systemic change and the here-and-now opportunities to forge relationships that are life-giving, empowering and promote mutual healing. I believe we are called to both, and that we cannot do one without the other.

“Conclusion,” page 184.

I hope you’ll take the time to read this book for yourself. It’s got me absolutely fired up. Not only do I want to get plugged into helping the unhoused here in Minneapolis, but I’m wanting to explore more on the topic of grace. We’ll see what I get up to.

Leave a comment